I am not tired and I am not quite awake. In the distance, the buildings look faint like the remaining traces of an erased drawing. Fabi and Jonte walk silently around the plane, muttering to each other.

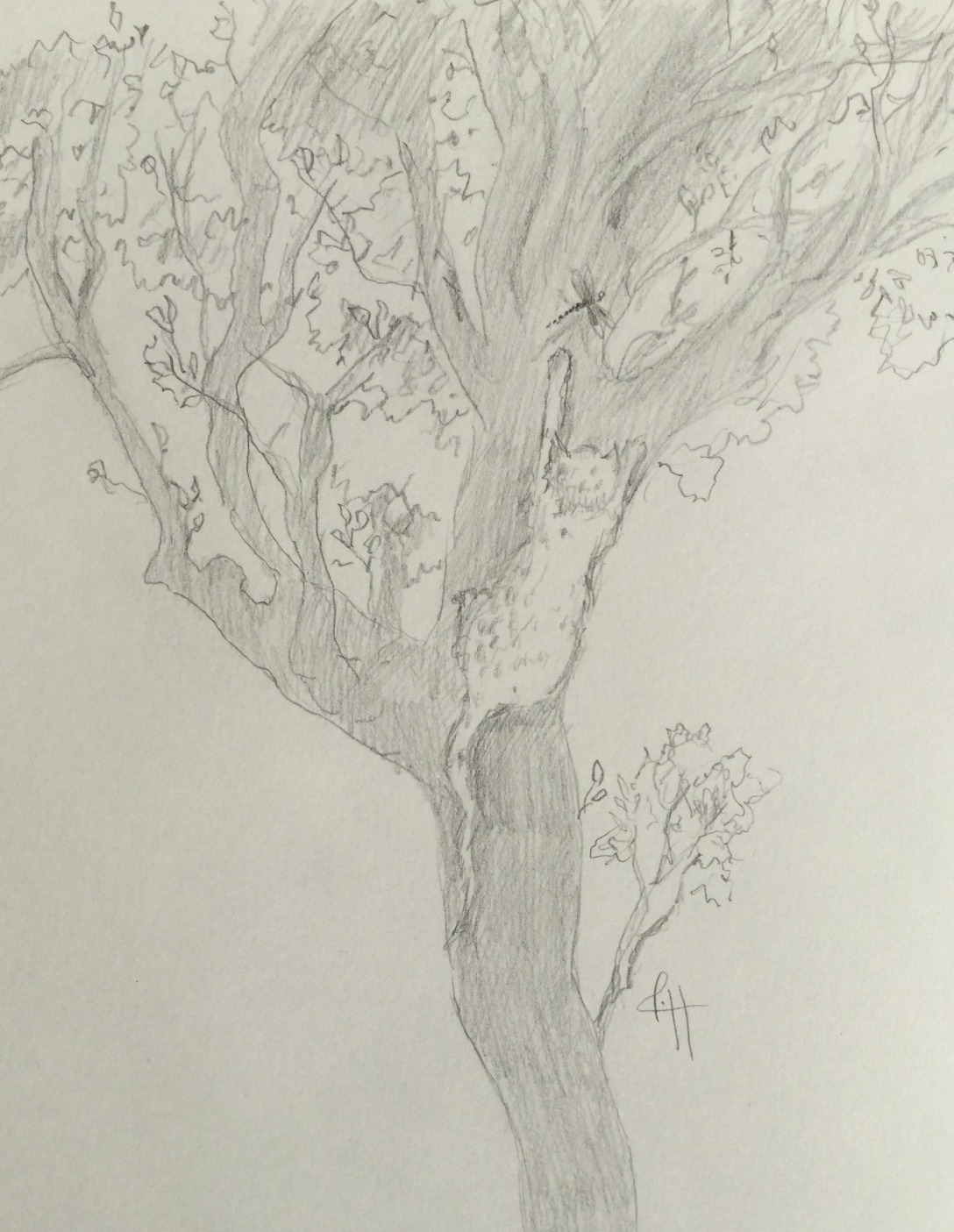

The fog lingers, as it always does. Fog is never in a hurry. It hides the beauty of the surrounding mountain peaks, and it doesn’t care.

Fabi stands under a wing and reaches up to unscrew something, I don’t know what. Anyway, it’s limited how long I can stare at Fabi’s plane before it starts resembling a toy, and the leap is short, in my mind, between toy and broken toy. Before I know it, I imagine the airplane tossed aside, like a dead bird with its neck and wings in odd angles.

But there is no way from here to anywhere, except through the air.

“Lilja! Are you keeping warm?”

It’s Jonte calling.

I try to sit up a bit straighter on my suitcase, and I try to smile, because I know I look haggard. The most important thing is that it’s clear that I’ve made up my mind.

“That’s good,” Jonte mutters, but he looks worried.

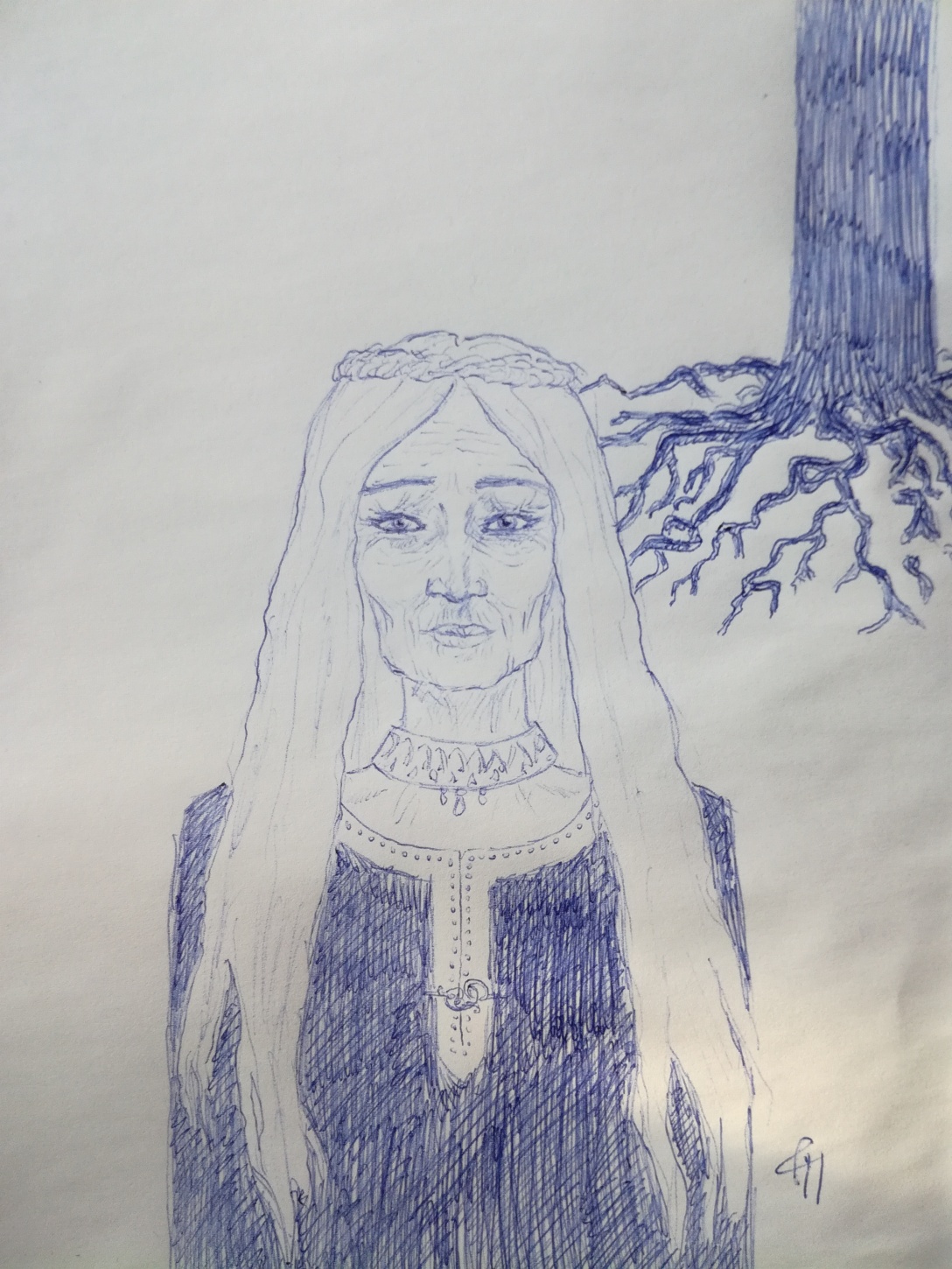

My body hates the raw, clawing cold. My lungs are crumbled up paper bags filled with rocks. I wrap my arms around my skinny legs. Around us, the fog has lifted ever so slightly. I can see a little further now, and I realize I’ve been absentmindedly looking for birch trees, and the outline of a boathouse, close to the summerhouse.

Inside my stomach, something turns over. No baby – I’m not pregnant, I never will be. But something, nonetheless, almost like another person, another and more sensible me, who wants to let me know I should have never left. I shuffle my feet a little, and dig my chin into my collar. I’m wearing my dad’s old bomber jacket, the one he had when he was a teenager and looked like James Dean. We look nothing alike, he and I, except we’re both blonde and blue-eyed, but that’s Sweden for you. Besides our colouring, we’re very different, not least when it comes to our views on the world. My dad is a small-town guy, not one for adventure. I know I’ve broken his heart.

The bomber jacket doesn’t smell like him anymore, but I’m still glad I stole it. It makes me feel like I have him with me, when the homesickness kicks in with waves of nausea, and I think I’ve made a terrible mistake. Sometimes it’s almost unbearable, how much I miss my family and common everyday things in familiar surroundings, back at our old, whitewashed brick house, in its unkempt garden, or in the summerhouse.

I’ve somehow managed to not give in. I know that when I return, my dad will never take their eyes off me again, or leave me unguarded by an assistant – not for a second.

The brick house where I grew up, back in Sweden, was the only brick house in the street. It always looked slightly weird in amongst all the brightly painted wooden houses. We lived there because my mom was afraid of fire. We had a fireplace, but it was only used if it was so cold there were ice crystals forming on the floorboards – we used gas heating instead.

I remember feeling I’d reached the apex of my teenage rebellion when I snuck a candle into the bathroom and lit it, with my unsteady hands, and then showered without keeping an eye on it. My heart was pounding so hard black dots started floating around in my vision, and I felt the room spinning. But I held out, finished my shower, and then blew out the candle. And I never confessed my crime.

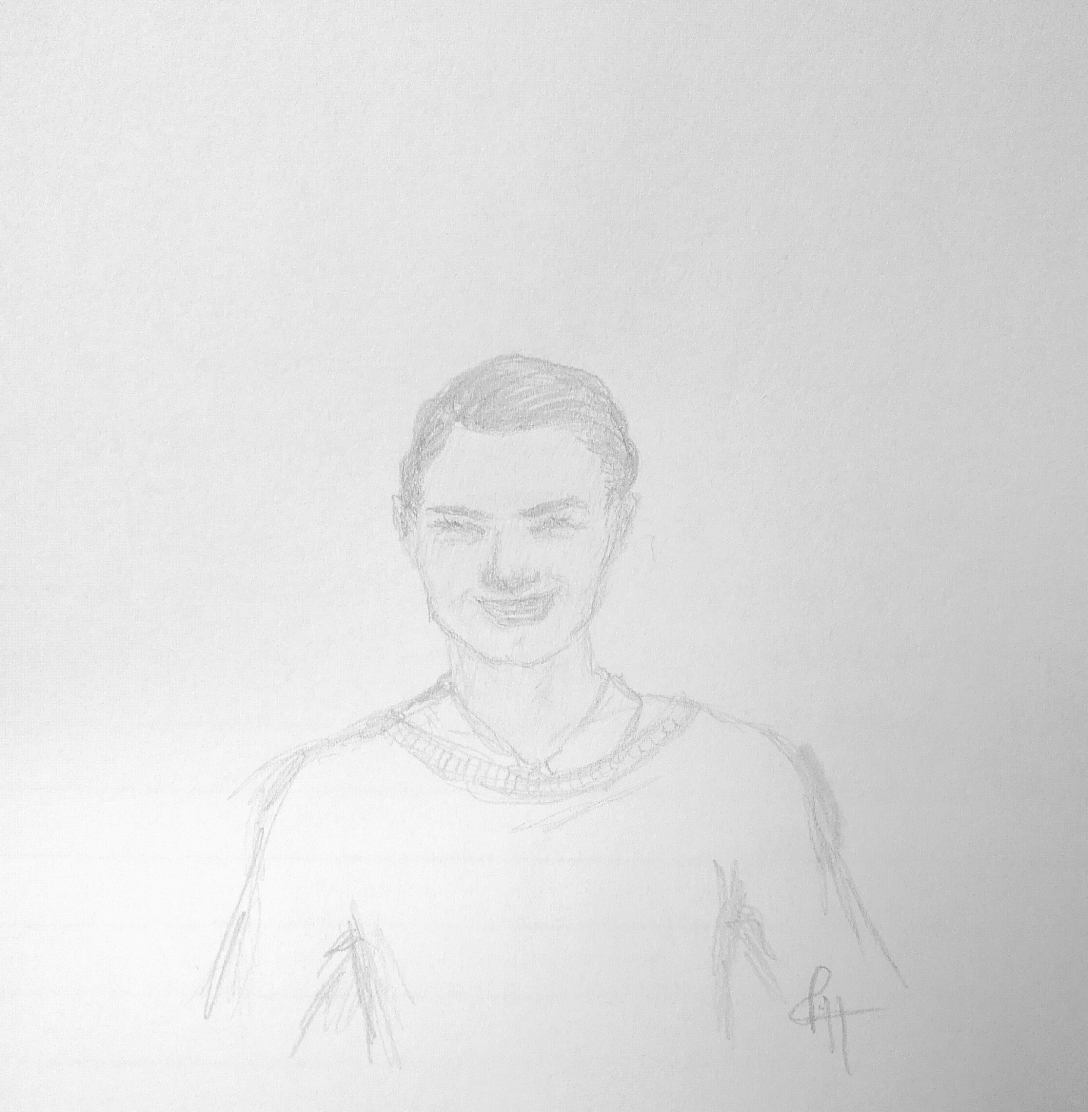

Jonte, or Jonatan, as the non-Swedes call him, was the one who taught me to exchange the word “fear” with the word “respect”. It has taken me a long time, but slowly, I learned no longer to fear fire, but to respect it; to treat it as the wild thing it really is.

I suppose Jonte would be surprised if he heard I learned it from him. He probably doesn’t even recall the conversation. Although he thinks more than anyone I know, he’s not an opinionated person, and he’s notoriously reluctant about giving any kind of advice. When you bring up a topic with him, most often, he’ll give you a broad, rambling, sometimes poetic, sometimes nonsensical reply – and by the time he reaches a conclusion, he’s normally long forgotten what actually started his monologue. But somehow the phrase came up, which has now become my personal anthem that I repeat in my mind when I’m afraid. “Don’t fear the fire – respect it.”

I’ve since started thinking about many other things in the same way. Heights, for example. The ocean. Speed. I prefer when Fabi drives, rather than speed-crazy Jonte. Fabi embodies the same sort of healthy respect for engines and traffic accident statistics and weather forecasts as I do. Well – as I normally do. The fog is an exception. We cannot respectfully go flying on a foggy day such as this, in a rackety little toy plane. The only respectful option was the one that recognized the danger the fog represented, and acted accordingly – by staying on the ground.

But I have always flown in the fog. Ever since I was born. Ever since my mother realized something about me wasn’t quite right, when I was about three months old. I try not to use medical language; it estranges people from me, and goodness knows I am isolated enough as it is. I have a speech impediment that makes it impossible to pronounce even the simplest thing fully. I was born this way, with a lack control over my voice, my tongue and my mouth. I’ll never talk like a normal person. That’s why I love Jonte so much. He’s one of a very small number of people I’ve met who initially understood that despite the way I talk, my mind is perfectly sound.

I can walk and move almost normally, but sometimes my head will roll over, and I easily loose my balance. And I have to sit still, mostly, like now, to make sure my heart rate doesn’t rise dangerously, which it does all too easily. My heart has always been like a ticking bomb – so I’ve overheard it said. (I’ve overheard a great many incredible things, too, because often people talk very freely around me, thinking I can’t understand what they’re saying.) It was flawed metaphor, “ticking bomb”. My heart will never explode. It will simply stop. Maybe when I’m twenty-three. Maybe when I’m twenty-five. Doctor Lindström didn’t think I’d live past five years of age, initially, so I know I’m living on borrowed time.

Jonte and Fabi’s flight checks are finally done. I get up from the suitcase and wrap my arms around myself, as if my dad is here to comfort me. Jonte comes over, asking if I’m ready, which I am.

“Are you cold?”

“A little,” I reply. “And your nose is pink.”

“Is it?” Jonte mumbles. “Lilja, are you sure you want to do this?”

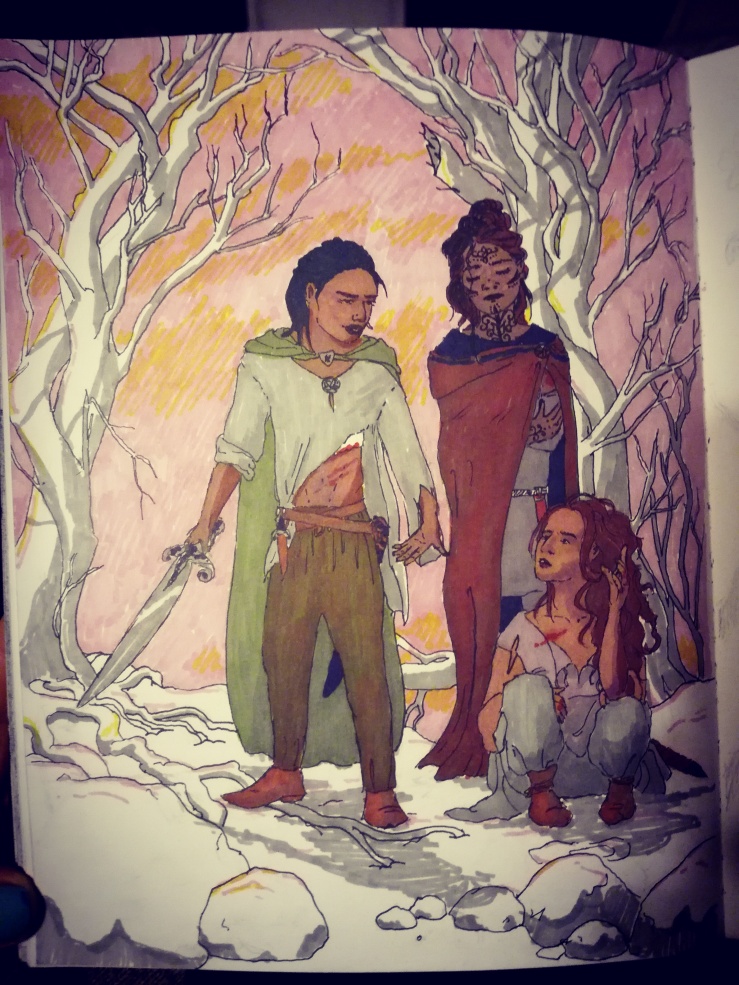

I’ve thought about it very thoroughly. Firstly, I know we must leave from here, because I want to see more of the world – I am terrified that the harsh winter up in the mountain will be more than my body can handle. Secondly, we all know there are no legal options open to us. We can’t fill in forms and write our names down. I am reported missing, and my parents and the Swedish police are working hard to track me down so that I can be kept safe. I’ll live the rest of my life in a cushioned cage, surrounded by guards twenty-four seven.

But that’s far too much to say right now. I lock eyes with Jonte, hoping he can see some of the things on my mind, regardless of how ill I must look.

“Yes, I’m ready,” I say.

Jonte helps me into the plane, and soon we are ready for take-off. Fabi turns on the engine and starts flicking switches. I am sitting in the back, unable to see his face, but I assume he’s rather worried. Being the way he is, though, right now I think he’s more concerned about breaking rules, than about the chance that we might soon be smashed against a mountainside.

When the tower realizes we’re about to leave the ground, they’ll shout at us. So far, they haven’t noticed that we weren’t just checking out the plane, but actually preparing for take-off. Nobody is allowed to fly in this weather, with a storm so close. But, as I argued to Jonte: If we don’t leave now, we could be stuck here for three months. When the snow has fallen, flight traffic all but ceases.

“We’ll be flying blind!” Fabi protested yesterday, when I told him that I wanted to leave the mountains behind. “You realize we could crash into another plane mid-air?”

“She realizes that,” said Jonte, whom I had already convinced. “But she says no other pilots will be stupid enough to fly now. We’ll have the sky to ourselves.”

“You’re insane!” Fabi exclaimed, stomping off in anger.

But he came back a few hours later, muttering, “So where would you wanna go?”

The engine roars, making the airplane rattle. I imagine Tuscany, wondering if it can possibly be sunny or golden at this time of the year. Through the scratched window, the sky seems to loom over us, enormous and heavy. Soon we will be in the midst of it.